Mt. Kenya – the Summit and Back – by Paul Birkelo

This is the third BRCK expedition I’ve had the privilege to participate in. As one of only two or three people on the now ~50 strong BRCK team who didn’t grow up in Kenya, I’m routinely amazed at the opportunities they’ve given me to explore this beautiful country. It’s always a privilege when you get to do the things you love and call it “work”, but doubly so when the team you get to work with is as dedicated and as much fun to travel with as the folks at BRCK.

Everyone who goes on a BRCK expedition has to have a job – a role to fill. In my case, it was logistics and media, specifically video. As with previous expeditions, we’ll be sharing a more in depth view of what it’s like to work with technology in challenging environments over the coming weeks as we edit the raw footage. My other contributions to the team had to do with the fact that I spent seven years as a whitewater rafting guide in Colorado before moving into the tech world, where I also spent a good deal of time climbing mountains and organizing expeditions.

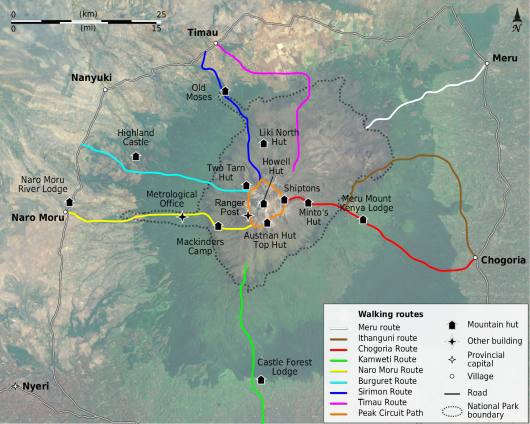

For most people, Kenya typically conjures up thoughts of wide open savannahs and lion spotting on safari, but it is also home to the second tallest mountain in Africa. The summit of Mt. Kenya stands at 17,057 feet, much higher than the tallest peak that I had ever climbed, the 14,433-foot tall Mt. Elbert, the highest point in Colorado.

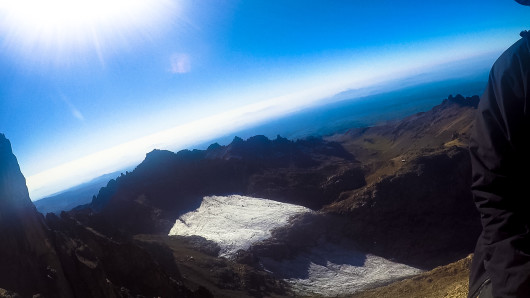

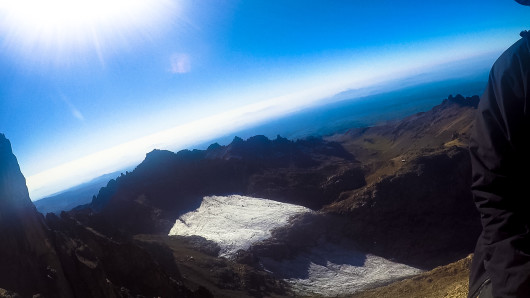

It’s also a stunningly severe mountain, with sharp, jagged peaks jutting into the sky, the remnants of an eroded volcanic cone. Kilimanjaro gets all the attention in Africa, at 19,341 feet above sea level, but it’s basically a big hill. Don’t get me wrong, it’s an impressive and very, very big hill, but you can ride a bicycle to the top. The majority of visitors to Mt. Kenya only climb to Point Lenana at 16,355 feet, as the two tallest peaks on the mountain – Nelion (17,021 ft.) and Batian (17,057 ft.) – require the use of ropes and high alpine climbing experience.

The long and short of it is that, while I certainly haven’t seen every mountain in the world, I have seen quite a few, and Mt. Kenya is hands down the most spectacular I’ve ever come across. As a lone peak – it’s nearest significant neighbor is Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, visible from the summit but still a few hundred miles away – Mt. Kenya is home to an entirely unique ecosystem. The Yellowwood forests at the base host buffalo and numerous other types of wildlife. We found elephant droppings and tracks as high as 13,100 feet while camping at Liki North hut.

The higher altitudes feature unique species of giant groundsels found only on Mt. Kenya. The eastern side of the mountain resembles a moonscape, and looks out on spectacular 2,000 foot-plus cliffs plunging into the Gorges Valley. The western side lays claim to the infamous “vertical bog”, where the trail winds through steep, muddy marsh and moorland. Near the summit, several glaciers (each getting rapidly smaller every year) empty into emerald green tarns.

Being one of only a few mountains of similar height positioned almost exactly on the equator, Mt. Kenya is of particular interest to meteorologists, ecologists, and climate scientists. There are a multitude of permanent weather stations all over the mountain. Kenya Wildlife Services (KWS), who manage the park that encompasses the mountain, do a rather good job of maintaining the trails (you won’t see the trash littering the hillside that you frequently do on other hiking trails in the region), and the huts are all well maintained. The Mountain Club of Kenya and various other organizations have put a lot of effort into preserving and limiting the human impact on the fragile ecosystems represented on the mountain.

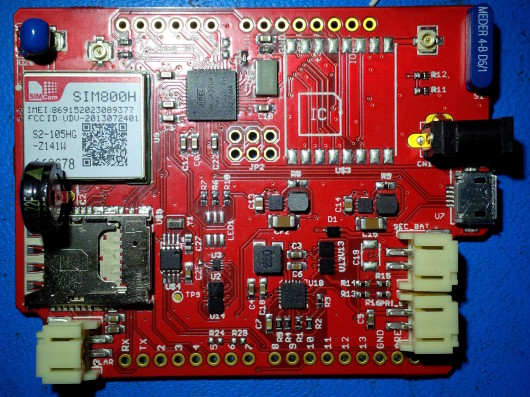

As you may have read in previous posts, BRCK started developing the picoBRCK in response to demand from a wide variety of people needing to live stream data from sensors in remote, hard-to-get-to and hard-to-survive-in places where electronics typically can’t be used. There are plenty of weather stations on Mt. Kenya, but many are roughly the size of a shipping container and require a permanent power supply and frequent manned inspection. These provide an incredible amount of information about the climate on the mountain, but only from a single point.

Many of the people we talk to require a much broader view of the ecosystems they’re trying to monitor – hundreds, even thousands, of very small, unobtrusive sensors feeding data in real time across hundreds of square miles monitoring water quality in the Mara River, tracking poaching kills via the presence of vultures, avoiding human wildlife conflict by alerting farmers to the presence of lions or crop-destroying elephants, tracking water distribution and the breakdown of remote irrigation pumps, or modeling micro-climates around mountains. To do these things, sensors need to be able to communicate across vast distances using existing infrastructure, be small and blend into the environment, be rugged and durable, fully self-powered, have no negative environmental effects themselves, and be extremely low-cost.

The picoBRCK is meant to do all of these things, and what better place to test its effectiveness than on the top of a 17,000 foot mountain? Unfortunately, KWS did not give us permission to leave the picoBRCK and weather station on the summit for a year, like we had hoped, and to be clear, that one data point would not have been particularly useful to climate scientists in and of itself. The purpose of this trip was not to revolutionize our understanding of the climate on Mt. Kenya – that might come later with the deployment of IoT en masse – but to test the picoBRCK’s capabilities outside the office, in a truly extreme and challenging environment.

The Climb

To do that, we were determined to put a picoBRCK on the summit, even if only for a short stay. Summiting a 17,000 foot mountain is no small task, especially when the last 1,000 vertical feet require technical climbing. True to BRCK style, our original plan was to go entirely unsupported – no porters, no guides, making our way on our own. That plan encountered a number of setbacks. With the six of us each carrying a 50 lb. pack, we still had two packs left over full of picoBRCK, weather station, and climbing kit. Like it or not, we were going to need some porters.

To make matters worse, Reg Orton (BRCK’s CTO) came down with appendicitis shortly before the trip. Reg, Kurt, and I were the only experienced climbers on the team, and Reg had the biggest rack (the collection of cams, nuts, and other protection that climbers use to stop a fall) and the most lead experience. Kurt had attempted to summit Mt. Kenya twice; he and his partner once got off route and the second time were turned back by weather and sickness. He knew the most about the mountain, particularly the fact that finding the route up Nelion can be extremely difficult. Most trip reports of unguided ascents recommend tackling the climb over a period of two days, bivying in one of a couple tin shacks bolted to the side of the rock face.

Without Reg, Kurt and I were forced to readjust our plans. We knew we would move slowly – I had never climbed a mountain this big, and hadn’t done a multi-pitch ascent with complicated route finding in over 10 years. The thought of staying the night at 17,000 feet was not a pleasant one. Even for someone in great physical shape, without taking the time to acclimatize to the altitude, it’s a guaranteed night of headache, nausea, and sleeplessness. It also would have made our trip take a minimum of 10 days, something our schedule at the office wouldn’t allow (we do actually have real jobs and real deadlines at BRCK, it turns out).

We were left with one choice – we needed to summit and do our testing in one day. To do that, we’d have to give up on making it to the true summit, Batian (17,057 ft.). To climb Batian at this time of year requires climbing Nelion (17,021 ft.) first, rappelling and traversing to Batian via the Gates of the Mist. Making that traverse would add hours to our day, something we simply couldn’t afford, so we set our sights on Nelion.

We would also need a guide. One of the things I like best about working with the BRCK team is getting the chance to share stories about Africa that most people in the rest of the world would never get to see. I routinely get to meet remarkable people doing remarkable things. Our guide Kim has been leading climbers up Mt. Kenya for 22 years. As a member of the technical rescue team on Mt. Kenya, Kim has saved dozens of lives (and even saved a few of our team when things went south later in our trip). A consummate professional, Kim provided all the rack we needed, and knew the route well enough to get us up to the top and back down in one day.

We met Kim at Austrian Hut on the southeast side of the summit the night before our climb. At 15,750 feet, the altitude was already getting to some of us. Steve and Jeff had stayed behind at Shiptons Hut that night (13,950 feet), after Steve started showing the effects of exhaustion and altitude. Leaving them around 2pm that day, Killah, Fender, Kurt, and I continued around the summit to Austrian Hut. The plan was for Killah and Fender to set up the weather station at the hut the next day, while Kurt and I climbed with the picoBRCK and our GPS tracker to the top of Nelion. We were all moving slowly and feeling quite miserable, so we didn’t think much of it when Fender climbed straight into his bag and went to sleep without eating that night.

After prepping our kit and going through the plan with Kim, Kurt and I woke at 4am the next morning to start our trek across the Lewis Glacier. It only took about 10-20 minutes to get across, but it’s steep and icy, so crampons and ice axe were required. One of the things we had hoped to do (and still might in a future expedition) was focus a webcam on the glacier to track its recession. Kim predicted it only has five years left before it melts away completely, and Kurt reckoned it’s at least 50% smaller than it was when he last climbed it 10 years ago.

After crossing the ice, it was a short scramble across a rubble and scree field to the base of the climb. This time of year, it’s summer on the south side of the mountain and winter on the north. Most people choose to climb Batian (the tallest peak) via the North Face Standard Route, but this was smattered with snow and ice when we were making our way up. The southeast face of Nelion, on the other hand, was getting baked by the summer sun. We encountered small pockets of snow and ice towards the top, but the rock was actually warm to the touch, and we both found ourselves sweating and shedding layers as we went up.

The climb itself was not actually technically difficult (don’t picture dramatic, overhanging cliffs where you have to pull yourself up by your fingertips). The hardest moves along the way are generally rated a 5.8 or 5.9 (using the American scale). But we were wearing boots, not rock shoes, and carrying a pack full of picoBRCK tech. Thanks to the altitude, neither of us had eaten or slept well in two days, and at 15 pitches (each pitch is essentially the length of a rope, at the end of which, the climbers have to build an anchor, swap who’s on belay, and start again) it’s a long climb. If we hadn’t had Kim, it easily would have taken us 20-plus hours to get up and down.

Luckily, Kim knew the route well enough that we were able to simul-climb at least eight pitches. Simul-climbing means tying to each other with the rope, but climbing together without belaying from an anchor. We moved much faster, but it meant if one climber fell, the other two would have to catch him without being anchored to the rock. Staring down a 1,000 foot vertical drop on either side while not being anchored is an exhilarating way to climb, to say the least. The southeast face of Nelion is a very exposed route, and we frequently found ourselves huddled on a ledge barely big enough for the three of us, gazing out into the abyss.

I’m sad to say, when we made it to the top, there was very little fanfare. The last pitch was a simul-climb, and we stumbled our way up to the tallest rock. With a muted “hurray”, we dumped our packs and sat down to rest our shaking legs. I had just set my new altitude record at 17,021 feet. Much as I wanted to be overjoyed, I was mostly focused on breathing. While Kurt and I tried to force down some lunch, Kim enjoyed a cigarette or two – he does this three times a week during the busy season and doesn’t feel the altitude at all.

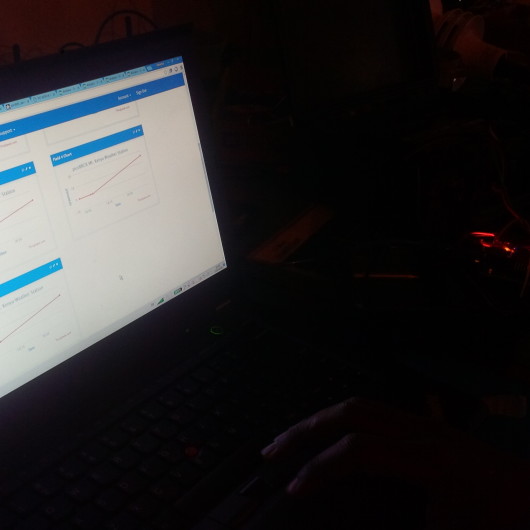

Kurt then broke out the picoBRCK. It was time to see if we were gathering and transmitting data like we hoped. Despite clear line of sight, though, we couldn’t get a lock on the nearest GSM tower. The picoBRCK was logging data, but it wasn’t sending. We were shattered, but had no time to troubleshoot the issue. Kurt is the lead electrical engineer at BRCK, and will share some of his insights into the technical things we learned on this expedition. For my part, I learned a lot about the constraints facing users operating in extreme environments.

When you’re cold and can barely breathe, having to remove fiddly little screws to access your technology isn’t an option. When you have to carry all of your kit on your back, every ounce counts, and needing to carry specialized tools (or any tools at all) is a problem. We actually removed the screws from the picoBRCK’s faceplate and replaced them with duct tape, so as not to have to carry an allen set. With extremely limited time in which to work, idiot-proof troubleshooting is essential. These and many more learnings will no doubt make it into the next revision of the picoBRCK’s design.

After about 20 minutes of admiring the view (and fiddling with the tech), it was time to head down. The route down consisted of about 14 rappels with a few down-climbs in between. The rappel points were bolted about 15 years ago, and the bolts are all in pretty good condition. The anchors all feel solid, though only a few have a backup in place. By the time we were heading down (around 1pm), the clouds had started to move in. I’ll never forget the second rappel. The first truly vertical ledge we stepped over, with fog hiding the bottom, all three of us wound up on a ledge maybe a foot wide, floating on an island in the clouds. To say it was a surreal, heart-fluttering experience doesn’t even begin to capture it.

The rest of the route down went without incident. We collected our crampons and axes at the foot of the glacier and made our way back across. We staggered back into Austrian Hut around 3:30 or 4pm. Despite being utterly exhausted, the sense of accomplishment was finally starting to hit us. We may not have made it to the tallest point on the mountain (Nelion is 36 feet shy of Batian), but it was an incredible experience, and the things we learned on this trip will come with us if and when we go back to make things work on the true summit. I will always be incredibly grateful to all of my colleagues, especially Kurt and Kim, for making this possible.

Speaking of colleagues, Kurt and I wound up back at Austrian Hut to find all of them gone. There was no sign of Killah or Fender, whom we had left in the hut that morning, and we had no idea if Steve and Jeff had made their way over from Shiptons that day. There was a huge mess around our room in the hut. My backpack had been torn into and stuff lay scattered. The mess kit and food were all still out and not cleaned. More perplexingly, the weather station was still up (the guys were to have taken it down and packed it back up by now).

It took Kurt and me a few minutes to realize that the first aid kit was also out (it had been buried in my pack), and that the guys had left behind things that they never would have left if they hadn’t been facing an emergency. We remembered that Fender had been moving extremely slowly when we came into camp the previous night, and hadn’t been feeling good when we all went to bed. The altitude was getting to all of us, and we knew that people had been airlifted off the mountain just that week after showing signs of acute mountain sickness and the beginnings of high altitude pulmonary edema.

Wanting nothing more than to rest, we packed everything up as quickly as we could and headed down to our rendezvous point at Mackinders Hut, about four to five kilometers away. Thus began a 22-hour odyssey to get everyone off the mountain as quickly as possible, ending in Nanyuki hospital. But I write this story safe and sound in Nairobi, and what happened in between is someone else’s to tell.

(Note: credit for the aerial photograph of the summit of Mt. Kenya above goes to Jeff Kirkpatrick – our guide, photographer, and biology teacher extraordinaire.)

Trying to catch the last rays of sun.

Trying to catch the last rays of sun.