It was 5 years ago that we created BRCK as a company, and I’ve had the great joy of being on a journey with some fantastic people, including the three here with me in this picture (Reg Orton, Emmanuel Kala, and Philip Walton).

We had an idea of what we were getting into back in October 2013, but none of us were sure where it would actually take us. All we knew then was that the barriers to creating hardware had dropped enough for us to get into it, that there was a problem in the internet connectivity space in Africa (and other frontier markets), and that we had the right mixture of skills, naiveté, and optimism to figure it out. Over the next 12 months we grew to a team of 10 that had this the desire to meet a big challenge and believed we could do hard things. As I write this, 8 of those 10 are still at BRCK.

In the intervening years we’ve built three full products and taken them to market (BRCK v1, Kio Kit, SupaBRCK), and a fourth (PicoBRCK) that is still in R&D. That alone is quite an accomplishment. I hadn’t known back in 2011, when the idea for creating a device was first hatched, just what the life cycle of building a hardware+software product would be. I do remember having a conversation with an old friend, Robert Fabricant, that I thought we should be done with the first one in about a year. He laughed and said it would be at least 2-3 years. He was mostly right.

[foogallery id=”4816″]

I’ve since learned that it takes approximately 18 months for a product to go through the concept, design, testing, productization, and first samples stages. Then it typically takes us another nine months for iterations and small fixes on hardware to happen, while that same time is spent concurrently hardening up the software side of things. For example, our most recent SupaBRCK took approximately almost two years from conception to product, and then another six months of continued fixes/changes to the low-level software and the hardware, before it worked well consistently.

Asking the Right Question

You would often hear us saying, “Why do we use hardware designed for London or New York, when we live in Nairobi or New Delhi?” as a way to frame the problem we thought we were solving. It was only in late December 2014, after we had shipped the BRCK v1 to 50+ countries, that we realized we were only partially on the right track.

It turns out the problem isn’t in making the best hardware for connectivity in difficult environments. Sure, that’s part of the equation – making sure that you have the right tools for people to connect to the internet. But the bigger question involves people. Who is connecting to the internet and who isn’t? If, after many years of building BRCK, we had built the best, most rugged and reliable solution for internet connectivity, that would be something we could pat each other on our backs for. However, if the problem instead was “How do we get the rest of Africa online?”, and we were able to solve that problem, then that was a legacy we’d be proud to tell our children about one day.

Sitting in our tiny office around Christmas 2014, we started thinking hard about this bigger issue and began doing deeper research into the problems of this loosely defined “connectivity” space. We started doing some user experience research, man on the street interviews, to figure out what the pain points were for people in Kenya.

Connectivity can generally be broken into two buckets:

First, accessibility – can I connect my device to a nearby signal?

Second, affordability – can I afford that connection?

The results were quite telling, it was definitely about affordability.

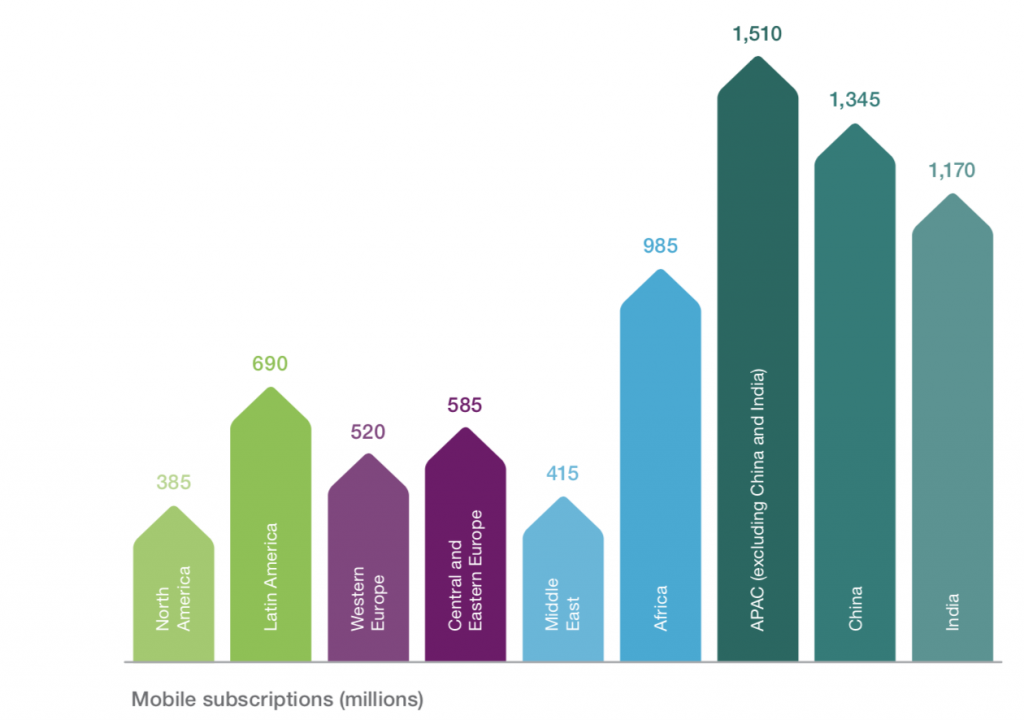

For everyone who’s not deep in African tech, let me lay out some interesting numbers for you. Accessibility in most of the emerging markets has been moving rapidly since the mid-2000s when we started to get the undersea cables coming into the continent. These cables then went inland and started a rapid increase in available internet connections and wholesale internet costs decreased rapidly. Since 2008, we’ve had more than one million kilometers of cable dug across the continent, and we have over 240,000 cell phone towers. Concurrently, the mobile device prices continued to drop globally, and by 2016 we started to have more smartphones imported into Africa than non-smartphones.

Reaching deeper into the market research, we started to study this affordability problem.

“A4AI found that the average price of 1GB prepaid mobile broadband, when expressed as a % of average per capita Gross National Income (GNI), varied between 0.84% in North America and 17.49% in Africa.”

It turns out that in almost every country in Africa, there is a consistent ratio among all the smartphone owners in a country: 20% could afford to pay for the internet regularly, and an incredible 80% couldn’t.

Interestingly, when we looked at who else was working in this connectivity space, almost everyone was focused on accessibility, not affordability. Those who were focused on affordability thought that just making the price cheaper was enough. What we’ve seen is that if you just make “less expensive” subscription WiFi (as most do), then you’ll capture another 10% of the market. And while that can make a profitable enterprise, it still leaves 70% of the market unaddressed.

This last blue ocean of internet users in Africa, as well as Asia and Latin America, is still largely ignored. Those who do have the resources to go after it tend to try with iterative approaches in both business models around affordability, and only marginal creativeness in solving for technology accessibility.

Moja Means ONE

It’s taken us 5 years, going through multiple iterations of new tech, building new hardware, and creating new software stacks that go from the firmware up to the cloud. We’ve been mostly quiet for the past year as we put our heads down and tried to take a new platform to market. Where are we now?

“Moja” means “one” in Swahili, and it was the brand name that we chose to call the software platform that we would build on top of the BRCK hardware. While Moja means one, “pamoja” means “together” or “oneness”, and that was the root we were looking for. To us, Moja is the internet for everyone.

We started by trying to make it work on the BRCK v1, but that was a bit like trying to make a sedan do a job built for a lorry (truck) – it wasn’t powerful enough. The SupaBRCK was envisioned as the hardware we could leverage that would allow us to not just have enough of a powerful and enterprise-level router, but a tool that was actually a highly ruggedized micro-data center. With this, we could host content on each device, as well as get people connected to the internet. Another way to think about the accessibility side of what we do is that we have a new model for how a distributed CDN works on a nation-scale, moving away from the centralized model that the rest of the world uses. In environments like Kenya, we can’t continue to just copy and paste models from more developed infrastructure markets, we have to think of new ways to deal with how the undergirding system actually works and operates.

We give the internet away for free to consumers. How does that work if we all know that the internet isn’t free? After all, someone always pays.

The business model is an indirect one. We charge businesses for some form of digital engagement on our Moja platform (app downloads, surveys, or content caching), and the free internet to our consumers is a by-product of this b2b business model. Like everyone else, we thought we could do it with advertising at first. But we realized that our unique hardware capabilities allowed us some other options, since advertising is a poor option for all but a few of the biggest global tech platforms.

Today we’ve deployed 850 of the SupaBRCK’s running our Moja software into public transportation (buses and matatus) in Kenya and Rwanda. They’ve been quite successful with almost 1/4 million unique users monthly in just the first three months. We have both a tested and working technology platform, as well as product market fit. With unit economics that make sense, a growing user base, and a business model that works, we’re excited for the growth phase of the business. This next step means going nation-scale in each of these countries, and also determining our next market to enter.

It’s important that ordinary people across Africa and other frontier markets can stop thinking about the costs of the internet and don’t have to turn off their mobile internet on the smartphones that they already have in their pockets.

Once they know they can afford it, the way they use the internet changes dramatically. An internet like this is feasible today, and it’s a cheaper, faster, more distributed, and resilient one. It’s also being built from the ground up in Africa, where we’re close to both the technology and human problems, and have a better chance of building the right thing.

Thoughts and Lessons Over 5 Years

First, make sure it’s a big enough problem.

If you’re going to spend 5+ years of your life on something, make sure it’s something that matters. At BRCK we are creating the onramp to the internet for anyone to connect to the internet, and a distribution platform for organizations trying to reach them. If we succeed we only succeed at scale, which by its nature means that we’ve done something big and that it has made a large impact on people.

Second, figure out what to focus on.

When you start out it’s difficult to determine product market fit. We started with a wide funnel of possibilities for our technology, industries that we could target and consumer plays. Over time, we were able to narrow down what could work, and what we could actually do, to the point where we focused on this big “connecting people” problem. We did detour into education with our Kio Kit, which we still think is one of the best (if not the best) holistic solutions for emerging market schools – after all, it’s in places across Africa, as well as the Pacific Islands and as far as Mexico. However, it proved to be too costly for our bottom line to hold inventory, sales cycles are too long, and it was largely a product sale. When we realized that, we started to focus most of our efforts on the bigger underlying issue across all of the markets, which was affordable connectivity and our Moja platform.

Third, persistence trumps skill.

Building hardware is hard. It’s even harder doing it in Africa. The upside, however, is that you’re both closer to the problem and that, if you succeed in figuring it out, you have a good head start on everyone else. The process takes time, costs money, and there are people and organizations who don’t want you to succeed. It always takes longer than you want to get software working properly, or hardware built and reliable. We’ve often been faced by that same problem that plagues all venture backed companies in Africa, in that you have to do a lot of education to investors to even raise the capital, and then when you do, you get charged a premium for perceived risk. Partner organizations take resources and time to work with, and they don’t always come through on their promises. All of these things (and more) mean that the best ideas don’t always win in the market, because it’s those that push the hardest and longest that win.

Fourth, it’s the people you do it with.

If you’re going to be on a journey that takes a great deal of time, with intense pressure, and where success is not guaranteed, then you had better do it with people that you can trust, who you can work with, and it helps if you like them too. Throughout my work career I’ve been more fortunate than most (whether at Ushahidi, iHub, or BRCK), and this time is no exception. I get to work with a host of wonderful people; not just smart and talented, but also genuinely good human beings. It makes work a joyful challenge, not an exhausting chore.

So, to those back in the day who believed we could do this when it was just a sketch in my notebook, thank you Shuler, Kobia, Nat, and Juliana (and the rest of the team at Ushahidi). To our investors who have joined us in this dream of connecting and doing hard things, you’ve continued to step up and that has made this possible. Thank you.

To Jeff, Janet, Birir, Kurt, Barre, and Oira, thank you for sticking it out for all these years and stepping up to more leadership challenges as we’ve evolved. To Philip, Reg, and Kala, I want to thank you for making the impossible happen, time and again, each for more than 5+ years.