Chasing the Sun (Days 3 and 4)

Catching up on a few updates at once here, you can read about Day 2 of our trip here.

It’s 6am in Lusaka, Zambia as I write this. The last two days have been a blur as we covered over 1,700 kilometers from Dodoma to Lusaka in what can only be considered as marathon sessions from sunup to just after sundown. Fortunately, both Tanzania and Zambia have some of the best roads we’ve seen, and the motorcycles and car all behaved well with only one slow puncture the whole way. We took small breaks every 100-200km in order to rest and move around a bit, but we’re still quite sore and ready for this day to do no travel.

The border crossing from Tanzania into Zambia at Dunduma left a little something to be desired. What felt like it should have taken about 1.5 hours at most, ended up taking 3+ hours, which meant our last 50km into a campsite were done in the dark on the only section of bad road we’ve seen. People did warn us of this, so it wasn’t unexpected. However, the reason wasn’t because of long lines of trucks slowing us down, it was due to inefficiency in the process itself at both immigration and customs.

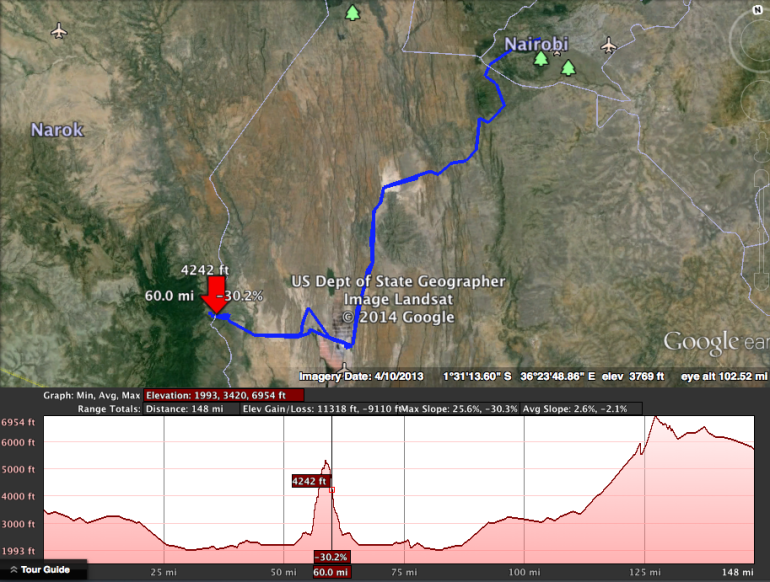

From here, our days get a little more sane, with a run down through Victoria Falls into Botswana and then finally Johannesburg. As an aside, it turns out that half-way between Nairobi and Jo’burg is almost exactly at a small town called Serenje, Zambia – 2,200km from each.

Time at Bongohive

We pushed so hard to get to Lusaka by now so that we would be here in time for the events at Bongohive, Lusaka’s tech hub, which were all scheduled for today.

1pm – Demo of BRCK (Philip Walton and Reg Orton of the BRCK team)

3pm – Meeting with Startups (Mark Kamauof the iHub UX Lab) – HCD, UX, DT

4:30pm – Meeting with Startups (Erik) – Investment readiness, experiences with Savannah Fund, getting into new markets etc

6pm – Keynote at Startup Weekend Lusaka (Erik and Juliana Rotich)

Lukongo Lindunda is the co-founder of the space, and we’ve known each other for years, since before they got it started back in 2011. I’ve been looking forward to seeing everyone here in the tech space for a while, and I’m interested in hearing what’s brewing in the startup scene.

Some of the startups that I’ve heard about from Zambia include:

- ShopZed.com

- Bantu Babel

- Venivi

- DotCom Zambia, BusTickets

- TeleDoctor

- SCND Genesis

If you’re part of the tech community in Zambia, I hope you can swing by, and we’re all looking forward to seeing you as well.

Lessons From the Trip

Since we’ve started this trip I’ve been thinking a lot about communications, as one would expect with a BRCK expedition, and especially mobile comms. We outfitted the truck with a omni-directional Poynting antenna on the front bumper, hooked up into the car, where we can also connect it to an amplifier if needed. As we drive down the road, we have a pretty good mobile WiFi hotspot, as long as we’re in range of a tower.

The last few years have seen a number of countries implement a registration process to buy SIM cards (ostensibly this is for security though it’s not been proven to be useful for anything more than big brother activities by governments). Even buying a SIM card is then a process of identification (usually passport or drivers license), so you have to budget for that 30-60 minutes to get that done, since it’s usually filling out a form by hand.

You then purchase credit for the SIM card and load it up – this is the easiest part.

Now you get into the “mystery meat” part of the process, which is how do you turn that airtime you just bought into internet credit? Each network in each country has a different way of doing this, some combination of USSD or SMS to get it going.

A couple things come to mind now when we look at the BRCK.

First, we need a terminal screen in the BRCK interface for us to do all of this from the device itself. Right now we find ourselves popping out the SIM card and using a phone (Mozilla’s 3-SIM phone is amazing for this purpose), and then inserting it back into the BRCK when done.

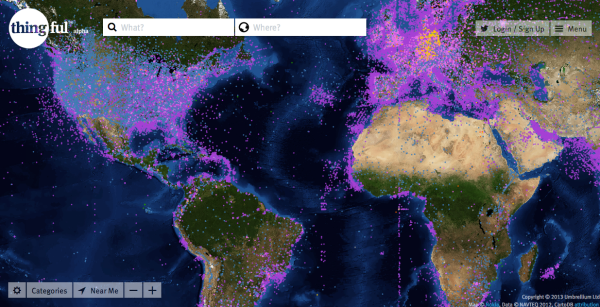

Second, there needs to be a database of this “airtime to internet data” information that we can all use. I’m not sure how best to get this going, but I know it would be immensely useful when you drop into a new country to have this at your fingertips.

We’re already working on the first issue, of USSD/SMS interface, but it’s complicated, so it’s taking longer than we’d like. This trip is about learning, and we’re already finding a lot of things to do better. Look for more posts on the BRCK blog from the others as well.

Much of Kenya is very dry, with dust and heat being a major concern for electronics, both things the BRCK is designed to handle. In Uganda, with an average annual rainfall of over 150cm in the highlands (compared to Kenya’s average of 100cm, mostly concentrated near the border), water and humidity are greater concerns. The BRCK performed admirably in these conditions, with no noticeable moisture buildup in the case despite 30°C heat, 96% humidity, boat spray, and even being dropped in the floor of the raft.

Much of Kenya is very dry, with dust and heat being a major concern for electronics, both things the BRCK is designed to handle. In Uganda, with an average annual rainfall of over 150cm in the highlands (compared to Kenya’s average of 100cm, mostly concentrated near the border), water and humidity are greater concerns. The BRCK performed admirably in these conditions, with no noticeable moisture buildup in the case despite 30°C heat, 96% humidity, boat spray, and even being dropped in the floor of the raft.