You’ve been hearing a lot about our recent trip to Uganda, and we’re not through yet! In addition to working with Hackers for Charity, connecting schools around Jinja, and wirelessly controlling underwater robots, we wanted to explore the IoT side of the BRCK, too.

A number of people we’re working with are keen on using BRCKs to remotely connect sensors and other objects to feed data back over the internet. Some of the uses we get most excited about are around conservation, ranging from tracking vultures to locate poaching kills to remote weather stations in the savannah.

Two projects we know of, Into the Okavango (http://intotheokavango.org) and the Mara Project (http://mara.yale.edu ; http://mamase.unesco-ihe.org), are deploying networks of sensors to monitor entire ecosystems. By tracking water quality throughout the Okavango Delta in Botswana and the Maasai Mara in Kenya, each hopes to improve our understanding of these fragile environments, and by publicly posting the data (as well as pictures of their own expeditions) on their websites, they hope to inspire further appreciation amongst those who may never get a chance to visit these amazing places in person.

When we first started talking about going to Uganda, home to the source of the White Nile flowing out of Lake Victoria, we knew we had to find a way to get out on the river and try our hand at collecting environmental data via the BRCK ourselves. It just so happens that Paul, one of the expedition team members, was a river guide for seven years in Colorado before coming to Kenya, and had found out about an expedition being planned by Pete Meredith down the Karuma to Murchison Falls stretch of the Nile.

This stretch is home to the largest concentrations of hippos and crocodiles anywhere on the Nile, and has been rafted less than 10 times in history, only once commercially. It’s home to some of the biggest, most terrifying whitewater in Uganda – a country known for big, terrifying whitewater. Uganda is also a country that is industrializing fast, with hydroelectric power stations playing a key role in meeting fast growing energy demand.

All these new dams mean that rivers in their natural flow are disappearing quickly. The Bujagali Dam near Jinja covered 388 hectares in reservoir, flooding several miles of pristine whitewater. A new dam under construction near Karuma threatens to seriously affect the wildlife that concentrate downstream, and the Murchison stretch may no longer be runnable after 2018. With almost 85% of Uganda’s population unable to access electricity, the case against building more dams is hardly clear cut, but it does mean the time to learn from, share, and experience some of the most unique ecosystems along the Nile is running out.

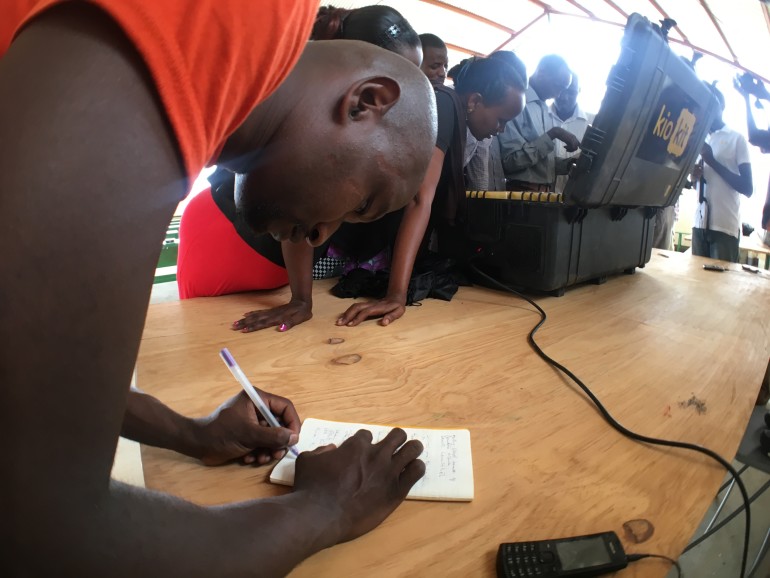

As a team of gadget-headed engineers, we figured a good first step would be to have an affordable, reliable platform for collecting and disseminating information about these ecosystems. While the BRCK itself runs on an Arduino compatible microprocessor, we included a blank AVR chip with direct access to the pins through a dedicated GPIO port on the back. In Jinja, our lead RF engineer Jackie quickly soldered up a pH and temperature sensor kit to a GPIO MRTR, and off we went.

After much debate, and despite being a generally adventuresome and outgoing bunch, the Murchison stretch proved to be a bit too much for some of our team, most of whom had never rafted before. (Mention the word “Murchison” around here and even the local guides have to suppress a shudder of anxiety. Pete is still planning an expedition for springtime, for those with a serious bug for adventure and not too tight an attachment to this world – http://www.nalubalerafting.com/expedition.html.)

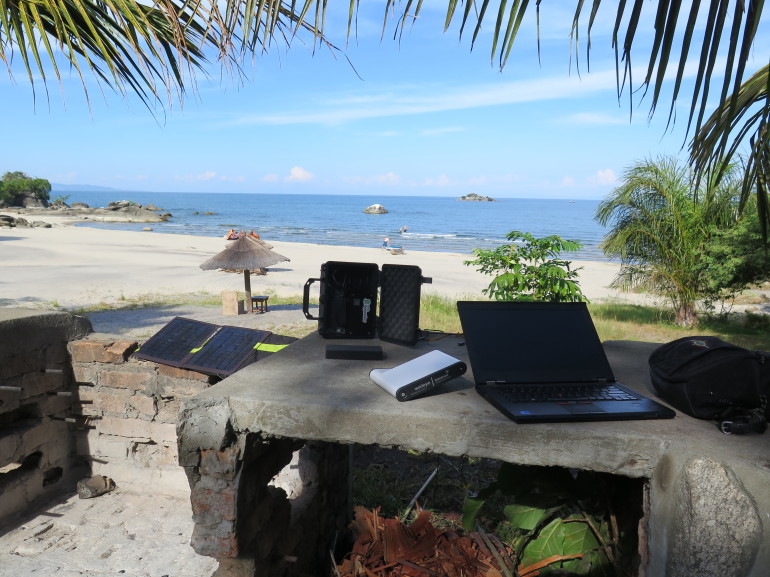

Instead, we opted to run the 30 or so kilometers of the Nile north of Jinja with Nalubale Rafting. Our goal was to get far enough away from “civilization” to test both the BRCK’s connectivity and the GPIO setup. The first day on the water, we hit five major Class IV/V rapids, including a three-meter tall, nearly vertical drop.

Along the way, we plugged in our MRTR and dipped our sensors into the water. Not being hydrological engineers ourselves, we weren’t quite sure what to do with any data we might collect, but we did learn some valuable design lessons around using the BRCK with the GPIO port (such as the need for a tighter connection between the MRTR case and the BRCK’s body). Ultimately, the hardware worked great, but some work remains on the software side to view our data on the web. We’ll be working on these tweaks and incorporating them, along with a means to visualize data fed through the port, into future updates.

After a hard day of paddling (and no small amount of swimming, only some of which was involuntary) we found ourselves at our campsite overlooking the river. It’s hard to imagine what this place will be like in 10 years. There’s nothing quite like eating dinner around the campfire, away from the constantly connected buzz of the city to make you appreciate the stillness of the wild.

As an expedition tech company, believe me, we get the irony. We still believe sharing these places before they disappear is the best chance we have for preserving them. There are far too many people who will never get to raft the source of the Nile, but we hope we can build a platform through which many more can experience it, if only vicariously.