The Lewa Marathon: My Experience

Camping, outdoor fun, and keeping fit are part of an undocumented culture within BRCK. You see, more than half our team is always very excited when there is an outdoor activity. The Lewa Marathon is a significant activity on our calendar and BRCK has taken part for the past four years. This experience is purely about spending time in the wild. From running the 21km marathon to spectating, it’s a wonderful three-day period. We got to bond with workmates, kids, partners, and friends, all with the goal of conserving our wildlife.

I have been to Lewa twice, the first time in 2018 as a spectator, cheering on my teammates. Little did I know that it would be me the next year. In 2019, I went as a runner, determined to race in the marathon. Yes, you read that right; I did 21km, and I survived!

The trip to Lewa involves several stops, but as Izaak Walton once said, “Good company in a journey makes the way seem shorter.” After a long drive, our team gathers at the campsite to set up camp. When we arrive, some members prefer going for game drives to enjoy seeing the beautiful wildlife. The Big 5 tend to come out in the evening so we had to take advantage. We saw a lion, elephants, buffaloes, and rhinos, among others. We were lucky to have our colleague Cyrus capture the amazing scenes and moments. The first night is usually relaxed and quiet compared to Saturday evening. This is because the runners need a good rest in readiness for the morning task. We usually have a bonfire set up as it gets dark.

Doing 21km is not an easy task and takes a lot of preparation. We started practicing in March, with monthly runs in Karura as a team. We encouraged each other on how to go the extra mile each time we ran. The first time we did a 10km run was my wake up call. I ended up walking for 9kms… Things had to change, so I started exercising three times a week. I would also run 10kms every two weeks to keep fit. It got easier with time and by June I was somewhat ready for the task that lay ahead.

My main goal was to finish, because those who had done it before told scary stories about the experience. We were up early on the chilly Saturday morning. I was super excited and nervous at the same time. We got to the starting point as a team and, of course, we had to capture the moment, which in the true sense turned into a mini photoshoot. Those who know me know my love for pictures runs deep. The warm-up dance at the starting line was so exciting and I had to keep reminding myself that I could do it.

Our motto at BRCK is “You Can Do Hard Things.” This was an arduous task, but I was determined to crush this milestone. I love project management, so I always end up dividing my tasks into smaller bits. The gun to start the race went off and I remember having a meeting with myself to affirm that I was competing with no one. I was running for a cause and all I had to do was to get a medal at the finish line. I didn’t start in a rush, I kept my pace for the first 12km and it was amazing. The hills from 14km were not easy, but I was determined to finish, so I kept going.

The organizers took great care of the runners. We had water points every 2km that also had energy drinks, fruits, and a cheering squad and, to be honest, this made the pain a little more bearable. I expected our team to be at every water point, but I was being too ambitious. But when I got to 10km, there they were. When I saw them, I think my energy levels tripled.

My legs decided to take a break when we got to 18km. 3km at Lewa is like 10km in Karura. I struggled to get to the finish line, it was the longest stretch I’ve ever run. I was tired and drained. The water and the fruits helped, but could only do so much. I did all I could to keep encouraging myself in the last phase, and I walked and jogged concurrently. I kept reminding myself that it would get better and before I knew it… I was at the FINISH LINE, having finished on my two feet and without dying in the process. The most exciting thing at the finish line is that you get a medal, a Safaricom gift hamper, a deep tissue massage and the pride of knowing you finished the race.

When it was all over, I felt extremely accomplished. I set a goal and I accomplished it, finishing the race in under three hours. Although I would have been happy to just finish, I also had a secondary motivation during the race… to finish before Paul Obwaka. You see, Paul is one of my colleagues and he made fun of me, saying how he could finish before me even if he ran in reverse. But as the saying goes, “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.” I ended up finishing two minutes before him and best believe I am enjoying the feeling of this moment.

If someone had told me in January 2019 that I would train and run a half marathon, I would have thought they were crazy. But now, a few weeks later, I know I am addicted to that feeling of accomplishment.

The hardest part is signing up, but BRCK made that process easy for us. So at BRCK, the thing that can keep you from succeeding is if you don’t show up and put in the hard work. Running and competing in the marathon offers so many benefits, so I will definitely do it again next year. It’s a habit I have added to my list. And if I can run a half-marathon, anyone can.

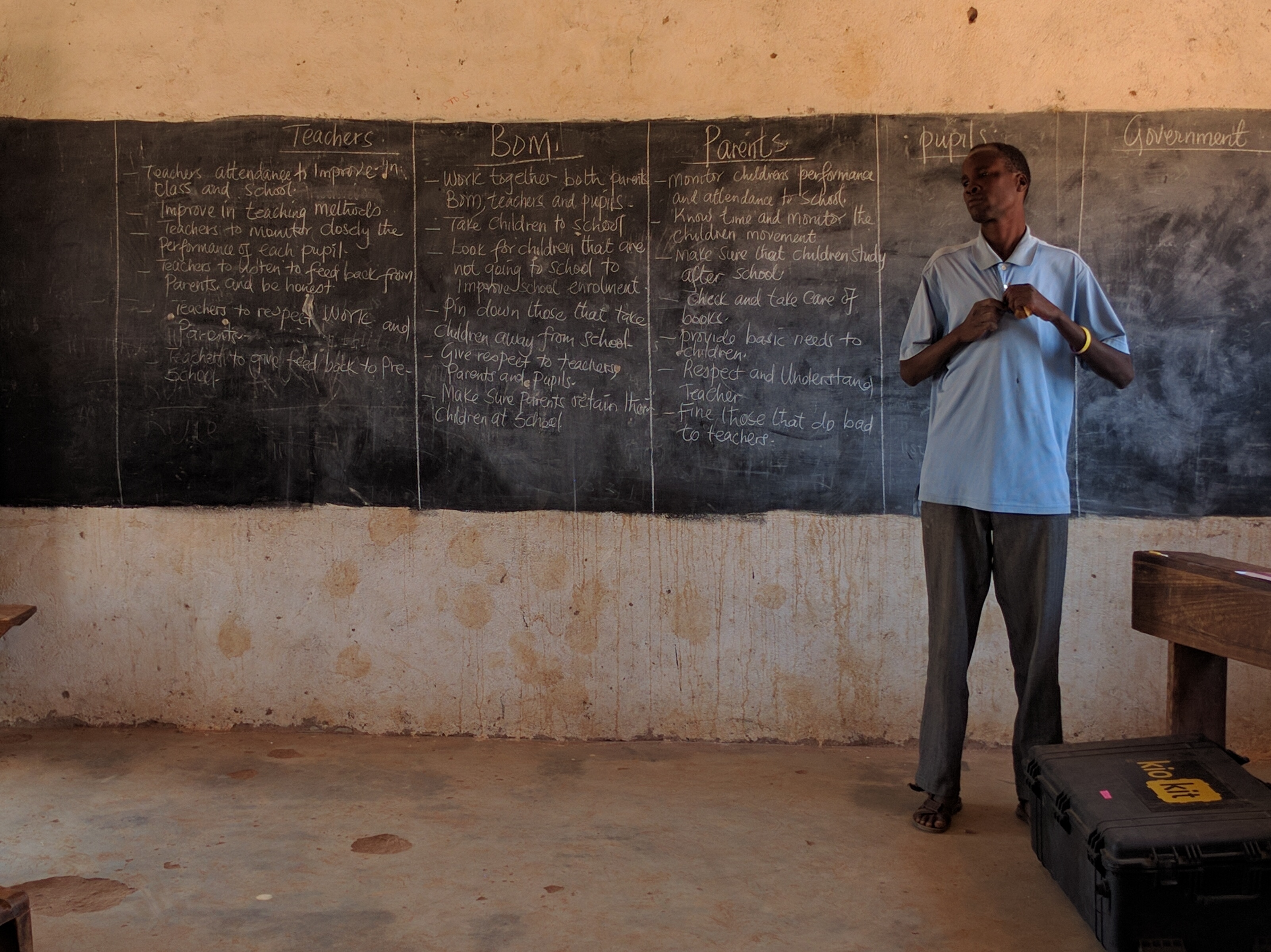

It is not just children who go to the school

It is not just children who go to the school

Sylvester (L) is also a teacher!

Sylvester (L) is also a teacher! L-R: Sylvester, Nivi, Edoardo. An important lesson from Samburu: the best herders are at the rear of their flock.

L-R: Sylvester, Nivi, Edoardo. An important lesson from Samburu: the best herders are at the rear of their flock.

Our surprise guest 😉

Our surprise guest 😉 Brian’s Place in Nanyuki

Brian’s Place in Nanyuki Inside Kalama Conservancy

Inside Kalama Conservancy (From Left) Amit, Edoardo, Mark, Nivi and Francesca

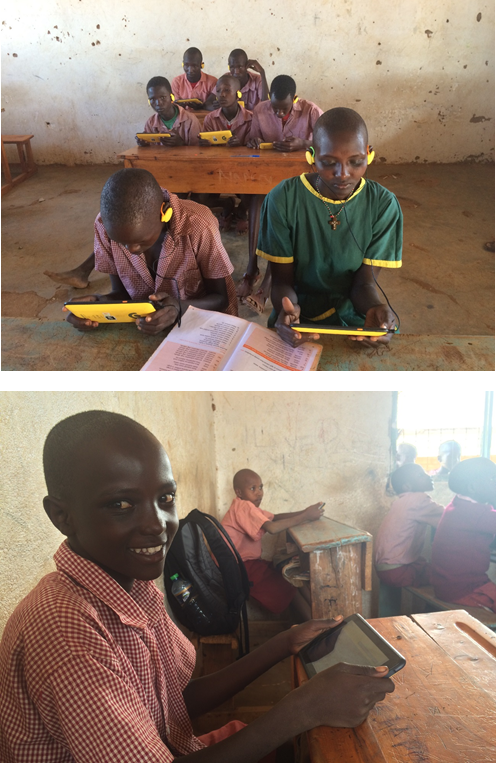

(From Left) Amit, Edoardo, Mark, Nivi and Francesca Teacher Elizabeth’s English Class

Teacher Elizabeth’s English Class Sprucing Up The Tent: Shower Setup

Sprucing Up The Tent: Shower Setup Preparing a most delicious dinner

Preparing a most delicious dinner